Klee and America at the Phillips Collection

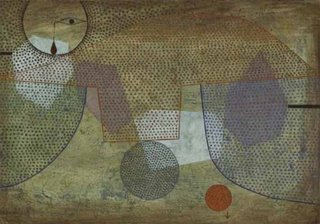

Paul Klee, Sunset, 1930.209. Oil on canvas. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Leigh B Block. ©2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo © The Art Institute of Chicago.

Paul Klee, Sunset, 1930.209. Oil on canvas. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Leigh B Block. ©2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo © The Art Institute of Chicago.Klee and America at the Phillips Collection

WASHINGTON, DC.- German artist Paul Klee (1879–1940) was one of Europe’s most internationally esteemed artists when the Nazi regime condemned his art in the early 1930s. At the same time, admiration for Klee swelled in America as his works increasingly entered the collections of major museums and private collectors. From June 17 to Sept. 10, 2006 at The Phillips Collection, America’s first museum of modern art, Klee and America will explore the rise of Klee’s American success and artistic legacy from the 1920s through the 1950s. It will reveal the reasons behind the enthusiasm for Klee in the United States, which provided not only his most attentive audience but also a safe haven for his theories of artistic freedom, self-invention, and authenticity. Unlike other European modern artists, Klee was never enraptured with American popular culture. By the same token, Americans remained largely dispassionate about the work of Swiss-born Klee when it was first introduced to the United States in the 1920s. By the end of the decade, only two major private Klee collectors existed in the country, Galka Scheyer in California and Katherine Dreier in New York. In 1924, critic Henry McBride underscored the enigmatic nature of Klee’s work, describing him as “that strange meteor from Switzerland” on the pages of the New York Herald. By 1930, when his art was being purged from the Schlossmuseum in Weimar, Germany, Klee’s reputation in America had already started to spread. His work was celebrated in Alfred Barr’s 1930 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the first one-person exhibition ever given to a living European artist at the museum. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, American collectors increasingly pursued Klee’s art, seeking works in greater quantities and of major significance. Today, more than ten percent of Klee’s entire output (approximately 1,150 works) resides in U.S. collections. Klee and America will investigate the long and complex history of Klee’s reception in the U.S. from the 1920s to 1950s, and the lasting influence of his work on American artists of the mid-20th century. Comprising some 80 works, the exhibition will explore why American collectors–including The Phillips Collection’s founder, Duncan Phillips–were attracted to Klee’s work, and how it came to be championed by the abstract expressionists of the 1940s and 1950s. It will open in conjunction with the focus exhibition When We Were Young: New Perspectives on the Art of the Child, which will feature contemporary children’s drawings alongside several historical childhood drawings by Klee and Pablo Picasso. “Duncan Phillips was a major believer in and collector of Klee’s works, even dedicating a room of the museum to the thirteen that he owned—all of which will be on view during the exhibition,” said Jay Gates, director. “Phillips recognized Klee as ‘a dreamer, a poet, and a brooding rebel…. No art can be more personal than the art of Klee.’ Today, The Phillips Collection continues its commitment to his artistic genius.” Klee and America is organized by The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas, where it received significant support from Altria Group, Inc. KLEE AND AMERICA - In the 1920s, Klee was well known throughout Germany and France as a leading figure of the European modernist movement. While the American media barely mentioned him, in Paris the pages of Broom and Vanity Fair heralded him as one of the fathers of dada and surrealism. By 1921, Klee was the subject of numerous publications and exhibitions throughout Germany, including a major retrospective at the Galerie Hans Goltz in Munich in 1920. He was also appointed to a teaching position at the Bauhaus school in Germany in 1921. Although a few years earlier he was considered one of Germany’s most highly respected artists, by 1933 Klee had been censured by Hitler’s Nazi regime as part of its campaign to stop the so-called “corruption of art,” and the market for his work collapsed in Europe. The National Socialist Society for German Culture dismissed Klee from the teaching position he had held at Düsseldorf Academy since 1931. He fled to Switzerland in 1933, but the Nazis still included 17 of his works in their “Degenerate Art” exhibition of 1937. Nazi Germany may have undermined Klee’s career and uprooted him from his job and home, but it did not distance him from his values. One reason why Klee appealed to American collectors and creators is that his life and works largely mirror American ideals. He was considered a revolutionary artist rebelling against a domineering nation, insisting on preserving his freedom of expression even in an increasingly oppressive environment. Though created on small canvases, Klee’s works shattered artistic conventions. Klee liberated artists from the grid of cubist space, infusing his work with a highly lyrical form of expression. Over time, he developed a powerful abstract language of signs that drew upon ancient sources as well as the energetic line drawings of children. The first Klee work acquired by the Phillips, Tree Nursery (1929), is divided into horizontal bands of color within a textured field of paint. By interweaving circles, triangles, and tree forms, Klee creates a lively inscribed text that resembles both a series of pictograms as well as the structure of musical polyphony. Drawing upon aesthetic design principles associated with the Bauhaus—and his own background as an accomplished violinist—Klee added to the emotional intensity in his work by expressing the visual analogies between art, architecture, and music. In Cathedral (1924), Klee uses delicate white lines to map the cathedral’s bays, windows, and crenellations onto a grid-like field, suggesting an architectural plan or elevation. At the far right edge of the panel, the lines become musical notations, evoking the harmonies of a choral song rising from a house of worship. Young Moe (1938) represents not only Klee’s love of music, but also his fascination with unusual materials. Rendered with colored paste applied to newspaper on burlap, the work pays homage to Albert “Moe” Moeschinger, professor of music theory at the conservatory of Bern from 1937 to 1943, who had dedicated three compositions to Klee in 1935. In this abstract composition, swirling black lines flow on top of shifting fields of color, implying a sense of rhythm and melody. Klee’s vast thematic and stylistic range appealed to American artists of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s wanting to escape the limitations of geometric abstraction and surrealism. A central figure in America’s embrace of the European avant-garde, Klee contributed significantly to what is now considered the essence of American art. In particular, Klee’s work was a major source of inspiration to the abstract expressionists, including Mark Tobey, Adolph Gottlieb, and Kenneth Noland. Other second-generation American modernists, such as Richard Diebenkorn and Alexander Calder, also cited Klee as having had a profound impact on their art. Increasing interest in and collection of Klee’s works in the United States during the first half of the 20th century may explain his assimilation into American culture that continues today. At the latest Klee retrospective, held in 1987 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, critic John Russell asserted that Klee’s influence was so pervasive that it would be difficult to pass a day in the city and not be reminded of his manner of signifying bodies and faces, his floating arrows and initials, and his shorthand architectures. "The legacy of Klee is everywhere," he said.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home